How Roof Orientation and Wind Direction Affect Storm Damage

How Roof Orientation and Wind Direction Affect Storm Damage

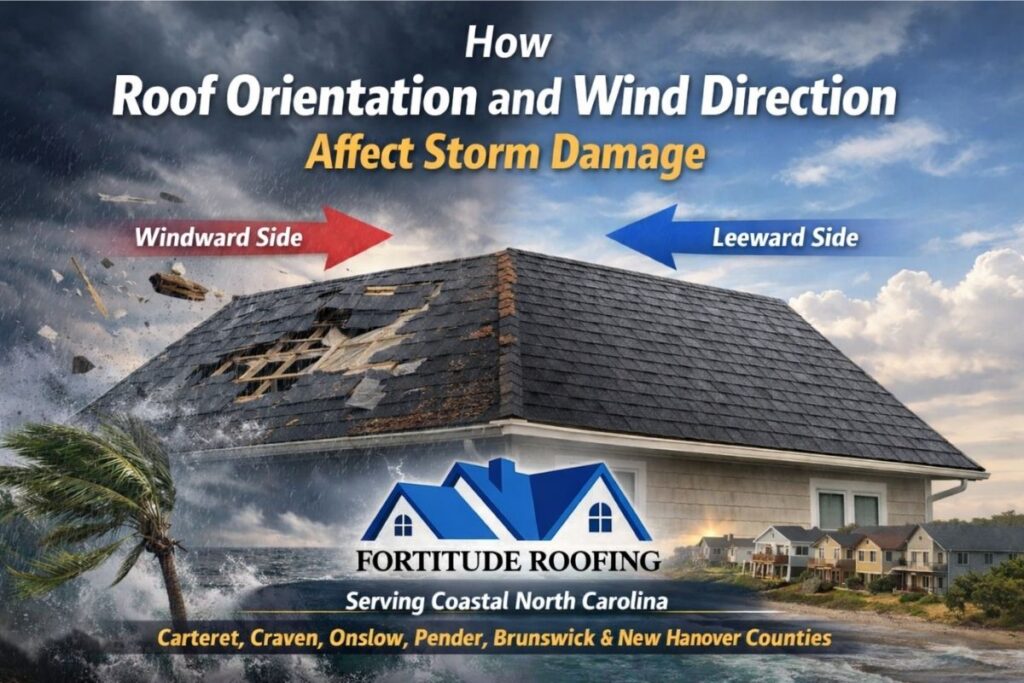

Storm damage is rarely uniform across a roof. Two homes on the same street can take different hits, and even on a single home, one slope can be heavily affected while another looks untouched. The reason is simple: roof orientation and wind direction control exposure, and exposure drives uplift forces, debris impacts, and where shingles lose seals or fail.

This guide explains the main factors professionals consider when evaluating wind-related roof damage and why asymmetric damage is common—especially in coastal North Carolina where wind events are frequent.

Fortitude Roofing serves Carteret, Craven, Onslow, Pender, Brunswick, and New Hanover counties.

Quick Answer: Why Does One Side of a Roof Get Storm Damage and the Other Doesn’t?

One side of a roof can be damaged while the other looks fine because wind acts directionally. Slopes facing wind and turbulence zones (ridges, edges, corners, and complex transitions) often experience higher uplift and debris impacts. Sheltered slopes may experience significantly lower wind pressure and can escape damage entirely.

Asymmetric storm damage is common—and expected.

Why Roof Orientation Matters in Wind Events

A roof is not impacted equally from all directions. Wind interacts with the home like water around a rock: it accelerates around edges, creates suction over ridges, and forms turbulence behind high points and obstructions. Roof orientation relative to wind direction determines:

- which slopes are windward versus leeward,

- where uplift suction is strongest,

- where debris is most likely to strike,

- and which areas will show seal failures, creasing, or missing shingles.

Key Factors That Drive Asymmetric Wind Damage

1) Prevailing Wind Direction and the Storm’s Wind Field

A roof’s most exposed slopes depend on the storm’s dominant wind direction (which can shift as the system passes). Professionals consider:

- which faces of the home were windward during peak gusts,

- whether the wind shifted (creating multi-slope damage),

- and how the home is positioned relative to open exposure (waterfront, open lots, ridge lines).

Practical implication: Damage patterns often “point” to the storm direction—missing shingles, lifted tabs, or creases tend to cluster where the roof took the brunt of the gusts.

2) Windward vs Leeward Behavior (Pressure vs Suction)

Wind damage is not only from direct pressure. Leeward slopes can experience strong suction and uplift.

- Windward slopes: can show direct pressure effects, debris impacts, and edge/rake damage.

- Leeward slopes: can show uplift suction, especially near ridges, hips, and transitions.

This is why it’s possible to see significant damage on slopes that did not face the wind directly.

3) Roof Pitch and Geometry

Pitch and complexity influence how wind loads the roof:

- steep slopes can experience different uplift dynamics than low-slope faces,

- gables, dormers, valleys, and intersecting rooflines create turbulence zones,

- complex geometry creates more edges and corners—high-risk areas for uplift initiation.

Rule of thumb: The more complex the roof, the more likely you’ll see localized concentrations of damage rather than uniform distribution.

4) Edges, Corners, and Ridge Effects (Where Failures Start)

Uplift forces often intensify at perimeters and high points. Professionals commonly see wind damage concentrated at:

- eaves and rakes (where uplift begins),

- corners (turbulence amplification),

- ridges and hips (suction zones),

- transitions and terminations (system weak points).

Even if most of a slope appears intact, perimeter zones may show lifted tabs, broken seals, or missing pieces.

5) Obstructions and Turbulence

Nearby features can shield part of a roof and intensify wind in other areas:

- trees and tree lines can block wind on one slope while creating swirling turbulence above the canopy,

- adjacent homes can reduce wind exposure on one face and redirect gusts onto another,

- parapets, chimneys, and roof-mounted elements can create turbulence and uplift zones downstream.

Result: One slope can look pristine because it was physically sheltered during peak gusts.

Why One Side Looks Fine (And That Can Still Be Legitimate)

Homeowners often assume “if one side is fine, the claim is weak.” That’s not how wind behaves.

Sheltered slopes may escape damage because:

- the wind direction didn’t load that face during peak gusts,

- nearby structures reduced exposure,

- the roof geometry prevented high uplift on that slope,

- damage concentrated at perimeters instead of the field area.

In many legitimate wind events, the roof tells an asymmetric story: concentrated damage where the storm loaded the system, minimal change where it did not.

How Professionals Document Orientation-Driven Damage

If you want a defensible evaluation (planning, repairability, or insurance), documentation should reflect slope orientation and wind behavior:

- Photograph every slope (wide + close-ups), not only the “worst spot.”

- Label slopes by location or compass direction (front/back/left/right or N/S/E/W).

- Capture edges and ridges intentionally (eaves, rakes, hips, ridge caps).

- Note obstructions (trees, adjacent homes, chimneys) and open exposure (waterfront/open lots).

- Tie findings to the storm window when relevant (date, when changes were noticed, leak onset).

A strong inspection explains not just what is damaged, but why the distribution is consistent with wind direction and exposure.

FAQs

Can wind damage occur on only one side of a roof?

Yes. It is common for one slope to take most of the wind load depending on storm direction, roof orientation, and exposure.

Why do ridges and edges get damaged first?

Wind forces intensify at roof perimeters and high points, creating uplift that can break seals and start shingle failure at edges, corners, ridges, and transitions.

What is the difference between windward and leeward damage?

Windward damage is influenced by direct pressure and debris; leeward damage is often driven by suction and uplift near ridges and transitions. Both can occur in the same event.

Does a sheltered slope prove the roof wasn’t storm damaged?

No. Sheltered slopes can escape damage entirely, especially if the storm direction and nearby obstructions reduced exposure during peak gusts.

Final Takeaway

Storm damage is rarely uniform. Roof orientation, wind direction, geometry, and obstructions drive asymmetric damage patterns. It is common—and expected—for one side of a roof to show meaningful wind damage while the other looks largely fine. The right evaluation explains the pattern and ties it to exposure and storm mechanics, not just shingle counts.

Fortitude Roofing Service Area (Coastal NC)

Fortitude Roofing serves homeowners across coastal North Carolina, including Carteret, Craven, Onslow, Pender, Brunswick, and New Hanover counties—such as Wilmington, Hampstead, Surf City, Jacksonville, Morehead City, Beaufort, Emerald Isle, Leland, Southport, and Oak Island.

Author and Review

Reviewed by: Fortitude Roofing (Coastal NC)

Educational content only. Coverage depends on policy language, endorsements, and carrier determinations.